Mawfadite is a term historically used in the Afro-Seminole Creole language. While documented evidence suggests that “mawfadite” was more commonly used in recent times to refer to gay men, the term itself hints at a more complex survival of pre-colonial recognition of gender diversity in both Indigenous American and African traditions.

Afro-Seminole Creole (also called at different times Shiminole, Mascogo, Seminole, or Siminole by its speakers) is a creole language historically spoken by the Black Seminole people combining vocabulary and grammatical influences from English, various West African languages, Spanish, Muscogee Creek, and other indigenous languages.

ASC is closely related to the Gullah language spoken on the Southeast Coast of the United States,- which developed on the rice plantations of Georgia and South Carolina as enslaved Africans learned the English language while also maintaining elements of the African languages they spoke.

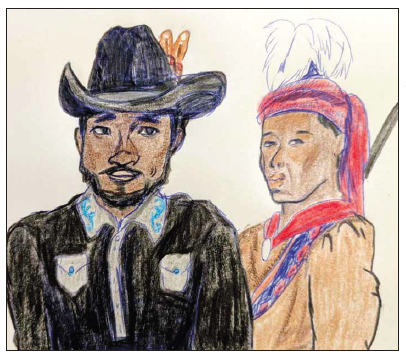

The Black Seminole are descendants of enslaved Africans who took refuge among the Seminole people of Florida in the 1700s and 1800s. These included those who escaped from American plantations in Southern states like Georgia and South Carolina, those who escaped bondage from the Creek Nation (some of whose members had adopted the practice of slavery from Anglo-Americans), and those who left settlements in Spanish Florida. The Seminole Nation itself was formed as an amalgamation of various peoples, including Creek people who fled European encroachment in Georgia and Alabama, other Indigenous refugees, survivors of Indigenous groups from Florida who had been decimated by colonization, and the African descendants who joined them.

Some Seminole people also practiced a form of slavery, although it differed significantly from the chattel slavery seen on American plantations.

The Black people living among the Seminole, as well as the products of Black-Seminole intermarriage, collectively came to be known as the Black Seminole. They developed their own culture combining African, European, and Native elements.

In the 1840s, many Seminole and Black Seminole were forcefully relocated to Indian Territory in present- day Oklahoma. Seeking refuge from the ongoing threat of slavery, a group of Black Seminole fled into the Mexican state of Coahuila, where they were given land by the Mexican government and formed the community of El Nacimiento de los Negros. Eventually, some of their descendants would return to Texas and form a community centered around the small town of Brackettville near the US-Mexico border. Today, Black Seminole communities can be found in South Texas, Mexico, Florida, Oklahoma, and the Bahamas.

The Afro-Seminole Creole language functions as an archive,- preserving various elements of Black Seminole history and culture and documenting aspects of the Black Seminole journey throughout the diaspora.

ASC was largely unknown to the outside world until a linguist named Ian Hancock, based in Austin, Texas, traveled to Brackettville in the 1970s and began documenting the language. Over decades of research, Hancock documented this unique, rich, and vibrant language through interviews with the elders who spoke it.

Today, Hancock’s work is being used as the basis for reviving the language among members of the Brackettville and Nacimiento communities.

One of the word’s documented by Hancock was “mMawfadite. In his notes, mawfadite was used to refer to “male homosexuals.” The word is clearly related to the term “hermaphrodite” (hemafrodita in Spanish)—an outdated word for intersex people now generally considered offensive. Hermaphrodite was historically used to refer to people who combinedexhibited both male and female characteristics.

Before European colonization, the majority of cultures indigenous to what is now the United States often accepted and embraced gender and sexual diversity. In many cultures, people who fell outside of the gender binary were common, accepted, and viewed as an essential part of life,- sometimes holding important ceremonial or cultural positions. Many Indigenous languages have specific terms for third or fourth gender categories that included people who we might today consider trans, nonbinary, or queer.

European colonists were often shocked by this widespread acceptance of gender and documented these traditions in ways that reflected their negative perspective perceptions.

Among the Timucua people of Northern Florida and Southeastern Georgia, Spanish colonists documented a third gender tradition. These people,- viewed within Timucua culture as a combination of both male and female,- were valued and assigned specific roles within their communities. The Spanish noted that they wore different colored feathers in their hair as a sign of their identity and social role. The Spanish spoke negatively of these people and used the term “hemafrodita” (or hermaphrodite) to refer to them.

By the mid- 1750s, the Timucua’s number had largely been reduced due to disease and warfare. Some Timucua survivors joined the amalgamation of Creek and other people’s that would eventually coalesce into the modern Seminole people.

Gender diversity has also been documented among the Creek, Yuchi, and other people who would form the basis of the Seminole.

Gender diversity also existed in pre-Colonial Africa. As in the Americas, traditions were diverse and varied among different ethnicities.

Many of those taken from Africa and forced into slavery came from the region of present-day Angola and the Congo. About 50 percent of the African words present in ASC come from languages spoken in this region, including Kikongo and Kimbundu.

The cChibados (sometimes called “quimbanda” by the Portuguese) are a tradition of gender diversity found among the Kingdom of Ndogo and other cultures in present-day Angola. Many chibados were people who were assigned male-at-birth but lived and presented in a more traditionally feminine way. They were allowed to marry men and – in some areas – were valued and viewed as fulfilling important cultural and ceremonial functions.

Queen Nzinga – a ruler of the Ndogo kingdom in the mid-1600s – was said to have “become a man” in some sources and to dress and rule as a one. She was noted for her strength and ability in battle and also for using her political power to keep many of her people protected from the Portuguese slave trade during her life time. According to some sources, she had multiple cChibados in her court and had relationships with many of them.

As in the Americas, many of these traditions were looked at negatively by colonial powers. Under Portuguese colonization, same-sex relationships and gender nonconformity were strongly condemned.

A lack of documentation makes it impossible to know to what degree these traditions survived among enslaved people brought to the Americas but forced conversions to Christianity and the brutality of chattel slavery and the plantation system would have made it difficult.

While the exact origin of the term Mawfadite is unclear, it points to a survival of various pre-colonial traditions of recognizing, acknowledging, and even celebrating gender diversity, as well as traditions that viewed gender diverse peoples as belonging to a third gender category combining both male and female elements.

The survival of this word in Afro-Seminole Creole hints at a further survival of an understanding of gender and sexuality rooted in African and Indigenous traditions. As with many words that may have previously carried a negative connotation, the potential exists for reclamation.

The language itself, carried and spoken by a people who traversed borders in search of liberty and self-determination, speaks to the interconnectedness between various ongoing struggles, including indigenous sovereignty, Black liberation, and migrant rights.

To learn more about Indigenous American traditions of gender and sexual diversity, one place to start is Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America (2000) by Will Roscoe.

To learn more about some African traditions of gender and sexual diversity, some places to start include Boy Wives and Female Husbands by Will Roscoe, Heterosexual Africa?: The History of an Idea from the Age of Exploration to the Age of AIDS by Mark Epperecht, and Before We Were Trans by Kit Heyam.

Follow the Seminole Indian Scouts Cemetery Association (SISCA) based in Brackettville, Texas and check out their website to learn more about the history and legacy of the Black Seminole Indian Scouts and the work that SISCA is doing to preserve this history and culture along the border at seminolecemeteryassociation.com. You can also learn more about SISCA’s Afro-Seminole Creole Language Revitalization Project.

Follow Casa de la Cultura- Black Seminoles to learn more about the work being done to preserve and promote Black Seminole history and culture in Coahuila, Mexico on their Facebook page of the same name